Paradox #1: How do I hold being both an earth-based Jew and a displaced Jew – a social location that inevitably leaves me as an occupier somewhere, in someone’s mind and embodied experience?

When I entered the field of environmental education in my late teens/early 20s, a set of implicit lessons were presented to me, some of which I unquestioningly accepted and some of which I tacitly endorsed while feeling there was something wrong: that connection with the natural world is beneficial for children; that the most beautiful places are hard to get to and often require special passes, gear or entry fees; and that romantic notions of wilderness are to be lauded and used as a barometer of connection to ecological systems that surround and sustain us.

What is wrong with this set of assumptions? In my opinion, they are all predicated upon a default relationship to land that presupposes a “right” to access green spaces, a “right” to define the boundaries of wilderness, and a “right” to be where we are, wherever we are. The source of this attitude of entitlement can be understood through cultural, religious and historical lenses. The effect of this attitude that I am most concerned about in my life and work is the reinforcement of settler colonial narratives in place-based education and movements for environmental sustainability.

I aim to disrupt, not reinforce, these narratives. Part of my practice of disruption involves relinquishing my internal sense of entitlement to be where I am. Part of my practice of disruption involves reading, listening, learning, analyzing, and quieting my own voice so that I can hear and support others’. Many native voices encourage me to return to my own earth-based roots; some support my doing that where I am a settler, while others suggest I literally return to where my ancestors came from. As a Jew inhabiting Turtle Island/North America, I find myself in a particular quandary in relation to this “return.”

I am deeply connected to my own earth-based cultural lineage and the physical homeland that birthed the indigenous consciousness, spirituality and metanarratives of Hebraic Jewish peoples (read Jewish Indigeneity Part I). I find part of the power of the modern Jewish environmental movement to be that we are applying the ancient earth-based wisdom of Torah to our current climates and contexts. Funding from the Jewish philanthropic world blesses us with the means to engage in collective cultural work that I do believe is beautiful and sacred. However, here on Turtle Island/North America, I am inevitably always doing this on someone else’s land. Paradox #2: How do I engage in my earth-based cultural narrative with integrity while the genocide of Indigenous people around me continues?

Another internal tension grips me. The Judaism practiced by indigenous Hebraic peoples had far more in common with Mesopotamian and Arab cultures than it did with the European Christian traditions that it got lumped with later on (e.g. the “Judeo-Christian” tradition). Through what Aziza Khazzoom (2003) calls “the great chain of orientialism” and through what I additionally understand as internalized oppression, the Jewish Semite replicated the orientalization project of which it was initially a target; having first been an early object of Western colonization, some Jews gained orientalizing power through Western hegemonic backing (fueled by structural antisemitism). One result of this process was the loss of earth-based Jewish wisdom and practice. Another eventual result was/is mass displacement of Palestinians. Yet another result is a global perception of Jewishness as white and Western, along with the marginalization of many Jews of Color and Jews of Arab and North African descent by Ashkenazi-centric Jewish society*.

This chain of orientalism has socially located me within a matrix of whiteness and privilege on one hand, and the trauma of colonization on the other. I mourn Palestinian displacement and deaths. I also feel anxious about what I consider to be a severe lack of understanding or acknowledgment (especially within progressive communities) of how structural antisemitism functions. I feel rage about Israeli policies of settlement and occupation. My soul also yearns for my homeland. I feel grief at how Jewish trauma is both product and culprit of this mess. And I feel fear expressing the part of me that still loves Israel, fear of being misunderstood, of being essentialized in a way that strips my story of its multifaceted truths. Paradox #3: How do I pursue justice from my positionality as both colonizer and colonized?

I do not have answers to these questions. I am living into them. I am curious if and how these questions resonate for you in relation to your own identities and ancestries. The legacy of colonization intrinsically impacts us all, from whatever continents and narratives we come.

*By Ashkenazi, I mean Jews of Eastern European, French and/or German heritage who have been racialized as white since the mid-20th century. See this work for my current (yet always evolving) perspectives on intersections of trauma and racism within the Jewish world.

[Note 8/19/18: Thanks to private comments and conversations, I’ve been learning more about the histories and identities of German Jews, whose experiences of othering/expulsion/dislocation make them targets of the same white supremacist ideologies and Ashkenazi hegemony that demoralize and oppress Sephardiot, Mizrahiot and other marginalized Jewish communities of color. My sincere apologies for any offense and harm I caused with my earlier categorization of German Jews as Ashkenaziot in this specific context of racialization and hegemonic power.]

Relevant Resources:

Abassi, A. (2017). Let the Semites end the world! On decolonial resistance, solidarity, and pluriversal struggle. In Jewish Voice for Peace, On Antisemitism (pp. 195-205). Haymarket Books: Chicago, Illinois.

Khazzoom, A. (2003). The great chain of orientalism: Jewish identity, stigma management, and ethnic exclusion in Israel. American Sociological Review, 481-510.

McLean, S. (2013). The whiteness of green: Racialization and environmental education. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien, 57(3), 354-362.

Decolonizing Jewishness by Benjamin Steinhardt Case (2018) https://www.tikkun.org/nextgen/decolonizing-jewishness-on-jewish-liberation-in-the-21st-century

************************************************************************

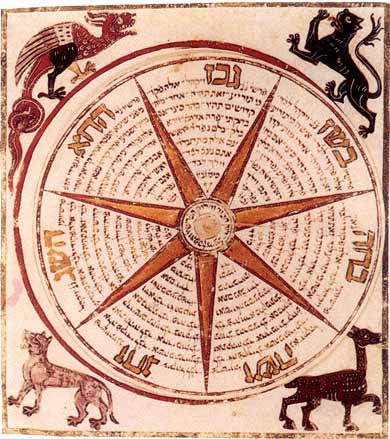

About the image at the top of this post:

“The inscription [on this calendar] indicates the length of main agricultural tasks within the cycle of 12 lunations. The calendar term here is yereah, which in Hebrew denotes both “moon” and “month.”

The second Hebrew term for month, hodesh, properly means the “newness” of the lunar crescent. Thus, the Hebrew months were lunar…The “beginning of the months” was the month of the Passover. In some passages, the Passover month is that of hodesh ha-aviv, the lunation that coincides with the barley being in the ear. Thus, the Hebrew calendar is tied in with the course of the Sun, which determines ripening of the grain.

It is not known how the lunar year of 354 days was adjusted to the solar year of 365 days. The Bible never mentions intercalation. The year shana, properly “change” (of seasons), was the agricultural and, thus, liturgical year…” (http://www.crystalinks.com/calendarjewish.html)