At the BKI, facilitator and educator Dr. Jonathan Cordero (Chumash/Ohlone) said, “White people talk about their rights a lot, but not so much about their responsibilities.”

Indeed, I myself often adopt a mentality of “I’m entitled to x ” — low-cost health care, being in a place at whatever time is convenient for me, filling up with organic peanut butter in the bulk section but labeling it as conventional, flying on airplanes, to name a few examples. All of these examples are pretty personal. They are about me. They are about what I have a right to as an individual.

What is the relationship between rights and entitlement? Between individual rights and collective responsibility? Many liberals think conservatives feel entitled to concentrated wealth despite the harm extractive capitalism has done and continues to do to people and this planet. Many conservatives think liberals feel entitled to getting services like college and health care for “free” despite the questionable economic efficacy of such policies. I am curious to discuss: What happens when we interrogate the very premise of “rights” as individual entitlements? What happens when we shift from thinking about what I am entitled to, to what we are responsible for?

I agree with people who say that guilt and shame are not effective primary drivers of social change policy or advocacy. I most certainly have waves of guilt and shame, but they are not the primary drivers of my actions and relationships, and I have enough self-awareness (well, I’m working on it!) that I can recognize when guilt and shame have taken over.

My sense of responsibility – in this case for supporting indigenous leadership – comes from the fact that the same system that enabled my immigrant ancestors to find relative safety and a spectrum of political rights in a new place simultaneously, through state and federal policies, displaced, dispossessed, dis-membered, and disenfranchised native people, as well as disrupted native families and kinship networks through forced adoption and abusive boarding schools. Many of the above policies are not in the books anymore as such. (If you know of ones that are, please Comment below and inform us.) Yet, in their quests for cultural continuance, indigenous people still face many of the same legal struggles in new forms, such as threats to the Indian Child Welfare Act, continued violations of treaties in the construction of pipelines and other energy infrastructure, and inadequate access to voter polls. Furthermore, these policies and practices definitively leave a legacy of intergenerational and historical trauma that result in disproportionately high rates of suicide and substance abuse among many indigenous communities.

I have benefitted from United States policies while others have been harmed. So what are my rights and responsibilities? I have a right to vote, and a responsibility to help ensure native people’s votes are counted, for example. I have a right to access clean drinking water and a responsibility to support efforts that enable indigenous people to steward ancestral lands and waters, as they have for thousands of years. I have a right to learn about and love my Jewish heritage, and a responsibility to support native people learning about and loving theirs.

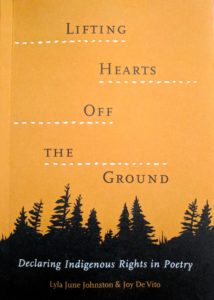

In Lifting Hearts Off The Ground, Lyla June Johnston (Dine/Cheyenne/European) and Joy De Vito (Canadian settler) unpack the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP) through poetry. Each poem in the book starts with the text of a numerated article from the UNDRIP, followed by a poem by each of the artists.

Article #2 reads: “Indigenous peoples and individuals are free and equal to all other peoples and individuals and have the right to be free from any kind of discrimination in the exercise of their rights, in particular that based on their indigenous origin or identity.”

Lyla June writes:

The old ones say:

Creator writes your rights

in the pages of

your life.

Read them in

the stars.

Listen to the voice

of the earth

when the snow melts

and the soil exhales.

She will help you understand:

You have no “rights” but

the right

to choose love

or choose fear.

Joy writes:

I immediately protest:

Of course you’re equal,

don’t accuse me of that.

Yet it needs to be written down.

It’s the way I see myself as the norm.

It needs to be written down.

Honestly asking: What do you believe you are you entitled to? What do you believe you are responsible for?

Learn more about the BKI and its parent organization Bartimaeus Cooperative Ministries. The photo featured at the top of this post is by indigenous Australian artist Safina Stewart (nee Fergie). She painted “Bartimaeus Billabong” for the 2019 BKI.